A few days ago a friend sent me this interview with Robert Sapolsky on free will. It was well-timed. I had already been thinking about the impact of my ancestor’s varied experiences on my own life and the two together clarified some ideas.

First of all, I believe in free will. I’m aware of the scientific arguments against it, both in the form of the interview above and in Sam Harris’ book that I read a few years ago. But my purpose isn’t to argue against those ideas per se—not least because I’m unqualified. I just want to develop a few ideas of my own here.

I grew up believing in what I would call a naive version of free will. In this version, a human makes wholly independent decisions that are thoughtful and purposeful. In such a view, a person might take into account other views or influences but does not necessarily need to. It’s a sort of radically free-floating free will. Homo economicus, in short.

This idea didn’t survive very far into my adult years. Buddhist ideas of interrelatedness, Wendell Berry’s ideas about community, and scientific ideas I learned from Sam Harris made it nonsensical to me.

Yet while I understand and appreciate the scientific arguments against free will, I don’t accept them—primarily because I don’t share the materialist assumptions behind them. Why should we believe that consciousness (a nonphysical phenomenon) bubbles up from sufficiently complex arrangements of neurons (a physical reality)? Far smarter folks than me have asked this question and have come to no satisfactory answer (see: the hard problem of consciousness).

I’ve said before that I think a person is a nexus of intersecting forces—parents, ancestors, friends, environment, culture, etc. There is no person apart from these forces. Nevertheless, it still seems apparent from human experience that free will remains, to some extent.

We often talk about free will as if it is an absolute possession—humans either have it or they don’t. What if, instead, it is a quality that has degrees?

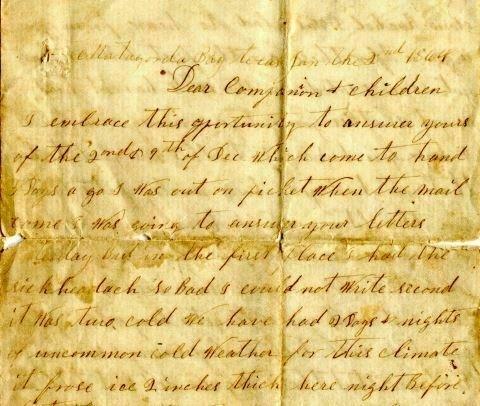

I’ve been thinking about this recently in connection to my ancestors, particularly my dad’s side of the family. While I don’t know a lot about them, as far as I can tell they were–for at least two generations and very likely more–poor, unhealthy, uneducated, and addicted to various substances. Dad’s childhood was hell for him and everyone else in the house—including the ones perpetrating the horrors, I’m sure.

Based on what we know about these patterns in families, it’s hard to imagine that this hell was created ex nihilo by my grandparents. For people in such situations, how much free will do they have? Sure they have some choice, especially in the mundane details of daily life. But how free are they in a larger sense? Not very, in my opinion. It is typical in these situations that the trauma is passed on, generation after generation.

Yet there is not zero freedom: my dad got out. He left that town and, for many years, his family of origin also. Nevertheless, some demons followed him out and he was not always successful in beating them back.

And so some of that intergenerational trauma lives in me. I hope now that my daughter, two generations from hell, will inherit still less of that trauma.

What makes the difference between being entrapped in circumstances and moving beyond them? I don’t know. I’m entirely unsatisfied with any variation on the boot-strap theory, which feels derived from the naive view of free will. I’m also uninterested in moralistic takes on these matters, so eager to assign blame that compassion is forgotten.

What if the key to a greater degree of free will is something like interior spaciousness? (That phrase is from Attuned by Thomas Hübl.) Again, how some people in the worst circumstances manage to attain that interior spaciousness while others do not is a fearful mystery. Nevertheless, it happens. Some people manage to cultivate a sense of curiosity and inward development. Some manage to see other possibilities than the ones immediately before them and the will to pursue them.

I agree with Sapolsky’s desire for a more compassionate world—but I do not agree that we reach that goal by denying free will and framing humans as biological machines. Interior spaciousness has the salutary effect of greater clarity and compassion. What if we arranged society in such a way that more people had the ability to cultivate it?