Rachel and I are continuing to research the lives of our ancestors of place. Today we looked into the Schroer family, who were the second family to live here (1939-1971). Dr. William Schroer was a chiropractor who moved to Bedford from Poland, Indiana, in 1927 to open a practice. He and his wife Delzena had one daughter Florine.

Dr. Schroer was a deacon of First Presbyterian here in Bedford. The family seem to have been socialites: very active in various clubs and committees. Dr. Schroer was a Mason and his daughter was a member of the Order of the Eastern Star.

We also visited their graves in Poland, Indiana, a little over an hour from here. They seem to have had deep roots in that little community, which was heavily populated with German immigrants.

This is just a sketch for the moment. I plan to write a more complete history of the house after I gather more information. Rachel and I were saying today that we have thought so much about our house and its history and people that it’s beginning to feel like a person in itself.

Young Schroers:

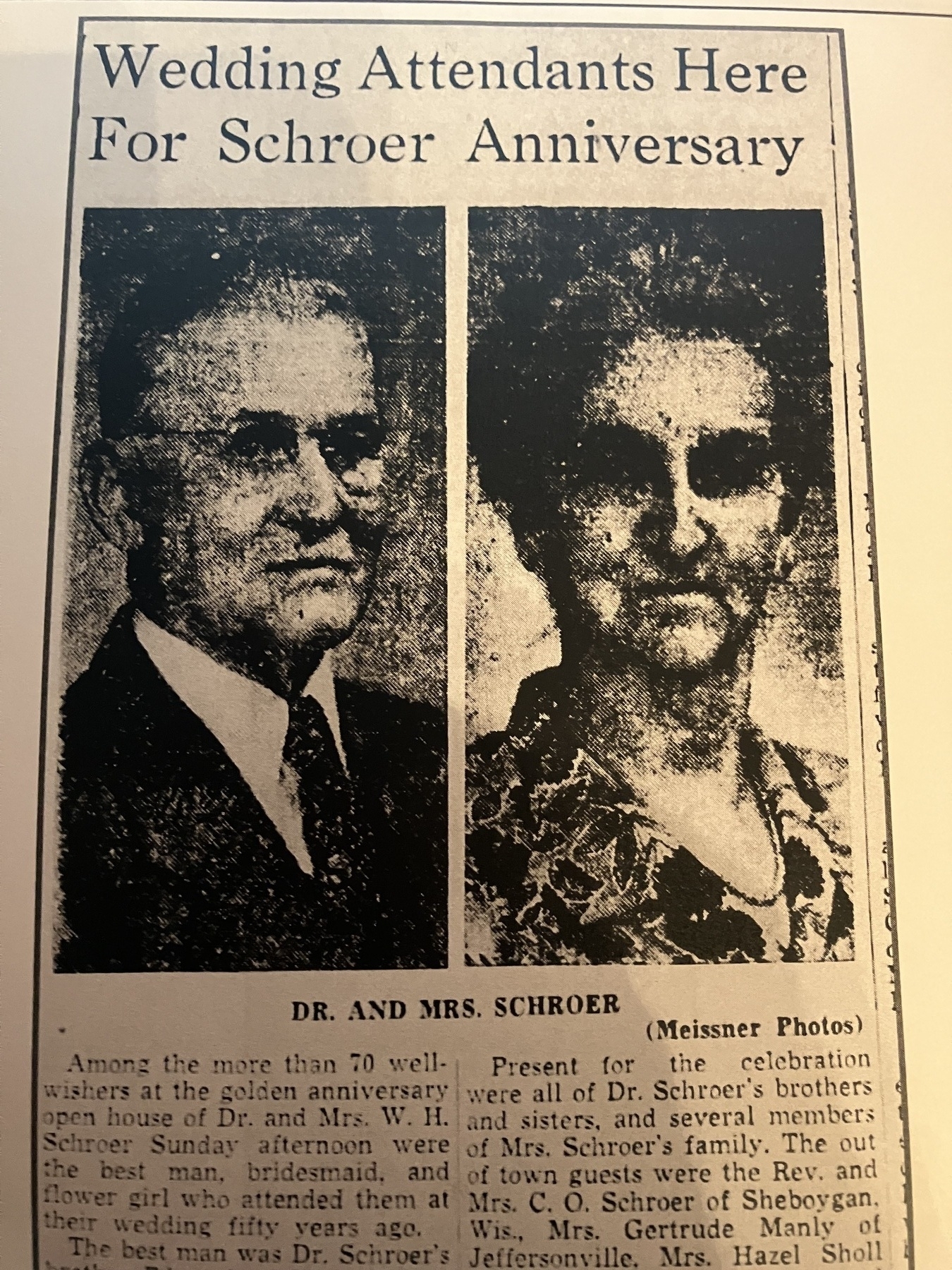

Older Schroers: