Helpful video comparing both health benefits and environmental impacts of dairy and plant-based milks. Short answer: if you don’t have any individual conditions that require one over another, oat or soy milk are best.

The “free range fantasy”

Dana O’Driscoll: Another challenge that many of us trying to move into sacred action face is what I call the “free-range fantasy.” In the same way that many people of previous generations were lured into the “white picket fence” narrative in the United States, those interested in sustainable living are often lured into the free-range fantasy today. The narrative goes something like this: You and your perfect partner decide to quit your day jobs, purchase 30 acres in some remote area debt free, and build a fully off-grid homestead complete with solar panels, acres of abundant gardens, fields full of goats, happy free-range chickens, and two cute children covered in strawberry juice.

Wendell Berry’s fateful decision

When reading books or watching documentaries about sustainable, regenerative practices, it is a matter of when, not if, a person will quote Wendell Berry. The impact he has had on the world is amazing. He has had obvious impact on the environmental movement and “back to the land” organic small farms. He was also highly influential on Michael Pollan and Alice Waters—who in turn have become enormously influential. Yet the Wendell Berry we admire might not have been.

The best hot chocolate

Makes two servings of rich, not overly sweet, hot chocolate. You’ll never use those packages of hot chocolate mix again. 1/4 cup sugar 1/4 cup dark cocoa Pinch salt 1/3 cup hot water 2 cups milk (I use oatmilk) 1 tsp vanilla (Optional) Large glug of Disaronno, Cointreau, or other liqueur Mix sugar, cocoa, salt, and hot water in a sauce pan. Stir frequently (and into the “corners” of the sauce pan because the cocoa will want to clump there) until mixture comes just to a boil.

My summer of not finishing books comes to an end

As I said earlier today, I finished reading In Limestone Country by Scott Russell Sanders. While I was recording that fact in my reading log (which stretches back to 2005!), I realized that it was the first book I’ve finished since April. To be fair, I’ve been busy and a lot of my reading over the past several months has been articles, etc., aimed at helping Rachel and me with our gardening project.

In Limestone Country by Scott Russell Sanders

Nothing makes the commonplace come alive quite like the work of a skilled writer. I’ve lived in limestone country all my life. I’ve heard the stories of how our stone built some of the great public buildings in America and brought prosperity to our area in the early twentieth century. Today, limestone monuments can be seen on buildings and in graveyards throughout Lawrence and Monroe counties. Porches, like mine, made of limestone.

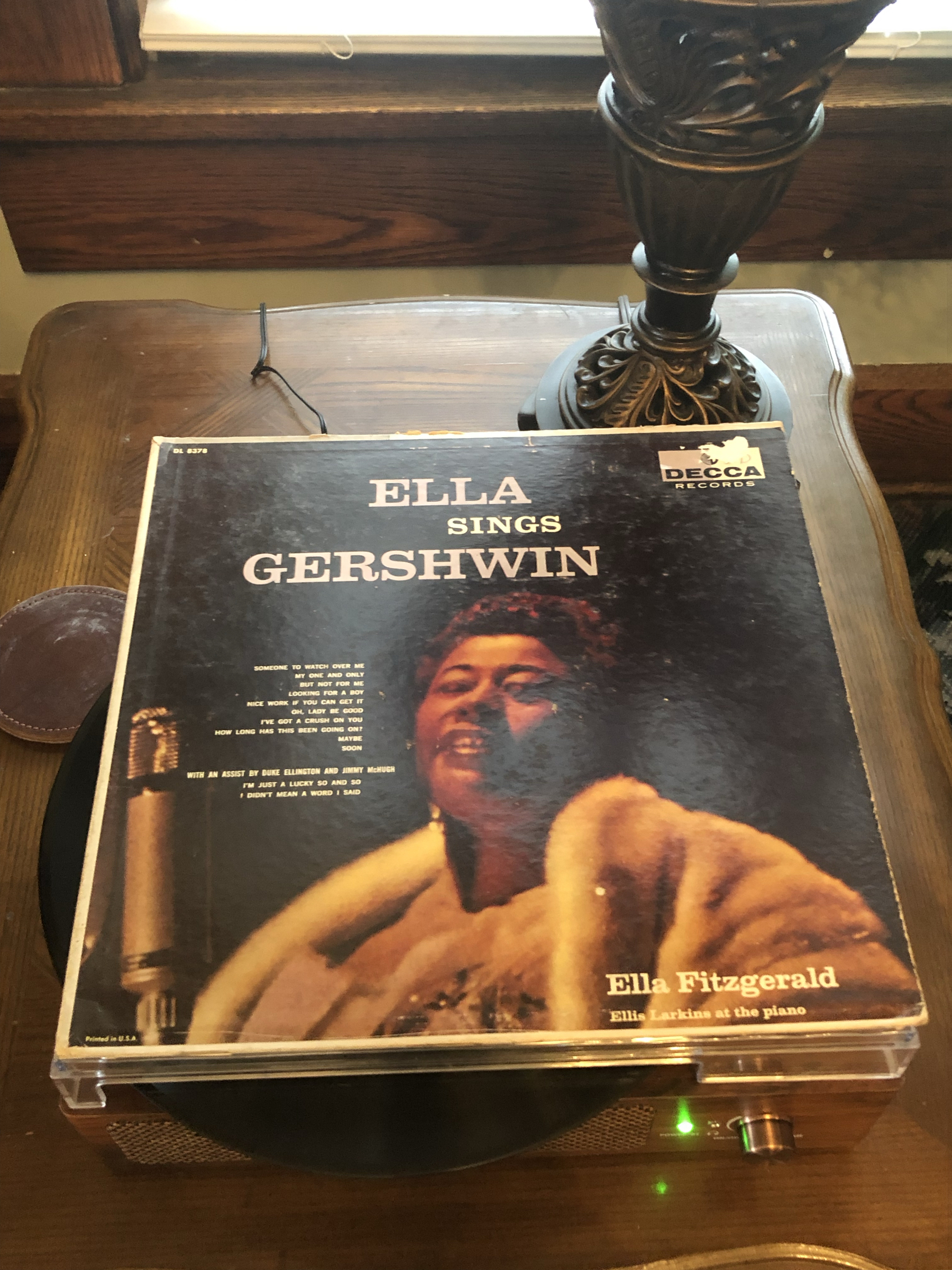

A quiet, snowy afternoon listening to Ella

So Amazon Drive is ending on 12/31/2023 and I discovered I have some mp3s hanging out over there from several years ago. What services do you all recommend for both storing and playing music files on an iphone?

Frank Brown Cloud has posted an excellent essay on the role of belief in our economy—particularly with regard to inflation. (Frank’s feed should really be in your RSS reader.) In the midst of his essay, he has this great aside:

Incidentally, this is why Facebook (& Instagram, & …) is designed to make users unhappy. The users of Facebook are the product that Facebook sells to advertisers, and an unhappy user is more desirable to advertisers than a happy user. By intentionally cultivating unhappiness in emotionally-addictive ways, Facebook can offer advertisers a premium product: the attention of people who are more likely to buy things as they attempt to fill an empty ache inside.