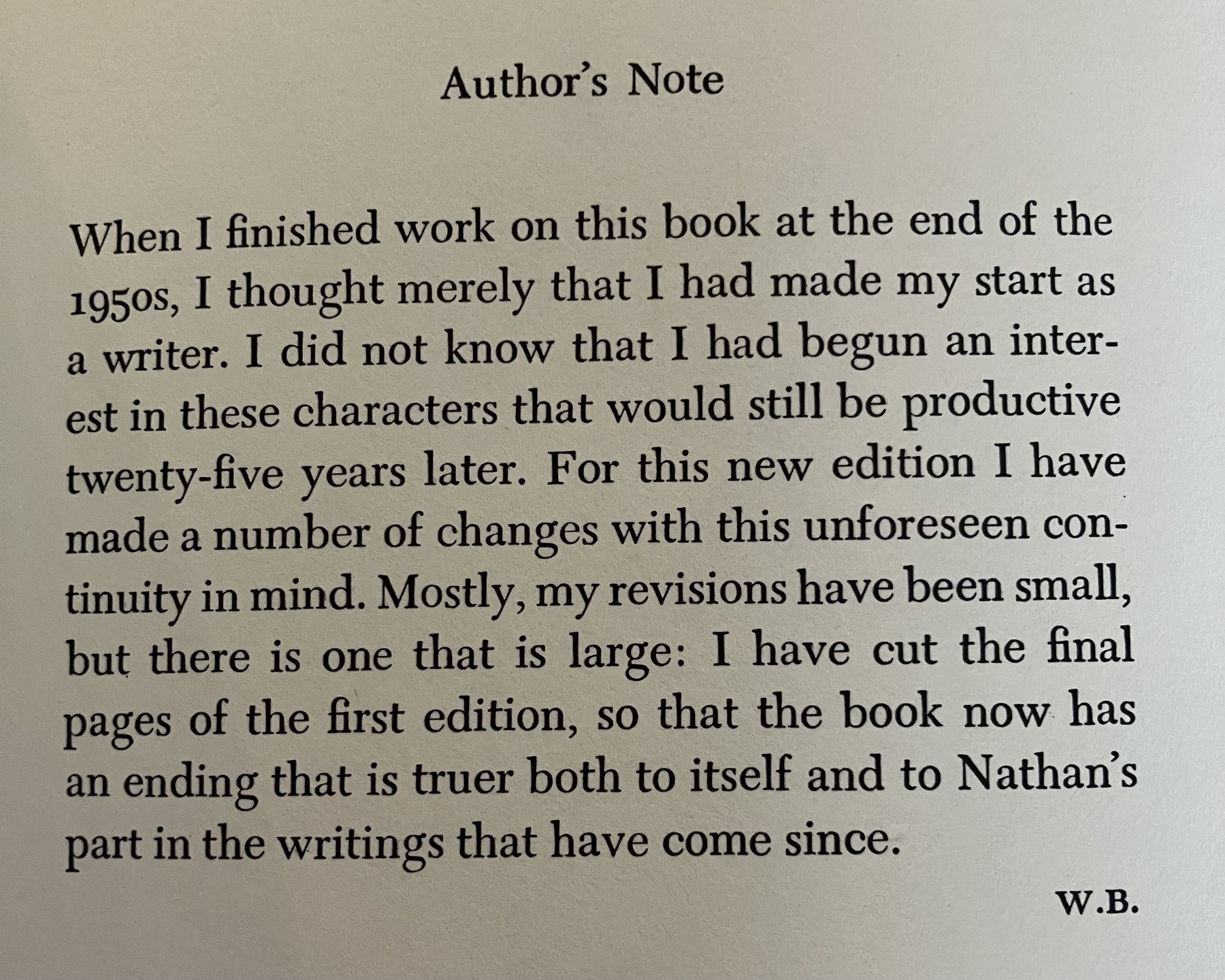

Finished reading Nathan Coulter by Wendell Berry. 📚 This was his first novel but my edition is the revised 1985 paperback. He edited it so that it would fit in what would become the overarching history of the Port William membership. I think I’ll read Hannah Coulter next.