Patrick Rhone: “The first approximation of others is ourselves.” Along these same lines, the most (the only?) profound thing I have ever heard in a corporate training session is that we always, always fail to realize how differently other people see the world.

“How do I live a meaningful life?”

Is there a state of life that is identifiable as “meaningful?” What does that look like? Is the questioner imagining a person who spends their time doing charitable work, or meditating, or finally making their way through their to-read list? But that may not count as “meaningful” for everyone. Those are generally seen as good things, but there are also a lot of other good things, some of which may be in competition with other good things.

An essential question: Who does this benefit?

One of the first questions to ask when you’ve uncovered an ideology is, “who does this benefit?” Let’s take the example from the linked post, that of activism as the only correct way to be an engaged citizen. Who would have an interest in perpetuating the activist model of constant engagement with the news, contacting legislators, attending protests, and voting? The following comes to mind: News organizations and social media companies have a direct, obvious, and well-documented stake in keeping your attention on their firehose of content.

Activism is an ideology

Whenever you bump into an idea that people seem to accept without knowing why and, in fact, bristle when it is questioned, you have uncovered ideology. Ideology is not always bad, but it is always worth investigating. Among American liberals today, there is a certain idea of what it means to be politically engaged: constant engagement with the news (reading news, watching news, doom-scrolling social media1), contacting legislators, attending protests, and voting (this latter takes on the quality of a sacrament and to question its efficacy is heresy).

One financial lesson they should teach in school is that most of the things we buy have to be paid for twice.

There’s the first price, usually paid in dollars, just to gain possession of the desired thing, whatever it is: a book, a budgeting app, a unicycle, a bundle of kale.

But then, in order to make use of the thing, you must also pay a second price. This is the effort and initiative required to gain its benefits, and it can be much higher than the first price.

From David Cain:

Self-imposed rules aren’t constraints, they’re good decisions made in batches.

That is a smart line.

This is a great post that I needed to read today. “My point isn’t that we’re not living in a Diet Dystopia, because I believe we are, but that my cynicism isn’t at all helpful. All it does is make me bitter and unpleasant, like a Caffeine Free Diet Coke.”

I Welcome Your Performance hypertext.monster

Alan Jacobs has recently posted about his news consumption habits in response to a worthwhile piece by Oliver Burkeman. Taking the latter first, Burkeman says that while there has always been alarming news, “the central place the news has come to occupy in many people’s psychological worlds is certainly novel”. Is this a healthy state of affairs?

Assuming you’re not reading this in an active war zone, it doesn’t follow that you need to mentally inhabit those stories, all day long. It doesn’t make you a better person – and it doesn’t make life any easier for Ukrainian refugees – to spend hour upon hour marinating in precisely those narratives over which you can exert the least influence.

What approach is preferable to marinating in the news? He discusses and dismisses both the “renunciation” and “self-care” approaches. Instead, he says, we should “adjust our default state”. Dip into and out of the news. Take action where you can and then move on. Then guard this practice with some “not-too-rigid” personal rules for handling the information. Rather than marinating in the news, do the good you’re actually capable of: “meaningful work, keeping your community functioning, being a good-enough parent or a decent friend”.

Burkeman’s rules involve putting physical distance between himself and his laptop and phone, along with time limits for their use. Jacobs describes his practices in his blog post:

- “Most important: I avoid social media altogether.

- I always have plenty to read because of all the cool sites I subscribe to via RSS, but not one of those sites covers the news.

- I get most of my news from The Economist, which I read when it arrives on my doorstep each week.

- In times of stress, such as the current moment, I start the day by reading The Economist’s daily briefing.”

I second Jacobs’ recommendation of RSS feeds. I use NetNewsWire and it really is a good way to keep track of writers and sites you’re interested in. Whenever something new is posted, it simply appears in the app and I can read it whenever it is convenient for me.

I also second his recommendation of avoiding social media. I’ve written before (and likely will again) about my discovery, once I closed the accounts, of how much my thoughts were driven by the timeline, not my own interests.

I avoid cable news at all costs. I believe it is, just as much as social media, engineered to hijack your brain. #CNNsucks

I tend to pick up most news through something like ambient awareness. If something is big enough, I usually hear about it one way or another. In times when I feel like I need to attend to the news (as in recent days), I typically go to the BBC news site because

- They have a reputation for being reliable and professional, and

- I don’t constantly hit paywalls, like at the NYT or WaPo, and

- It’s not jammed with video and ads. Again, #CNNsucks.

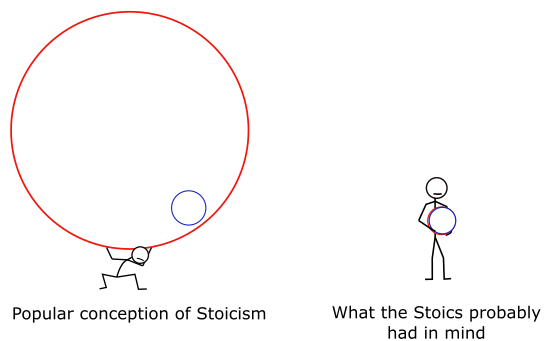

For me, it is an essential practice (and Burkeman refers to this) to continually distinguish between what I can and cannot control. I have little to no control over much of the awful shit that happens in the world. There are a few practical actions I can take. Beyond that, though, my responsibility is to learn (both for myself and with my family and friends) how best to navigate and understand the world we find ourselves in. It is useful to remember that, if life is the Battle of New York, I am not Thor or Captain America or even Hawkeye. I’m not even the NYPD. I am one of those people in the background scrambling to avoid falling debris.

Boredom is everything, man. I think our loss of boredom in contemporary society is one of the greatest, weirdest, ambient losses. It is one of these things that’s hard to quantify the value of. And we’ve lost it so completely and totally that we very rarely have moments to even re-experience it, unless you do so intentionally. And so for me, yeah the boredom of these walks is, I would say, 50% of the value of it. It’s forcing yourself into a place where you’re not teleporting mentally.